In the 1990s, Sweden reformed the pension system1 , and payments from the new system started in 2003, while Norway is in the middle of a pension reform that will come into effect from year 2010. The Norwegian reform is similar to the Swedish in certain respects, both in process and outcome. On the other hand, there are also some striking differences between the two countries, although they traditionally have followed each other closely in the development of Social Insurance schemes. I will describe and discuss some important similarities and differences between the two countries, with the ongoing Norwegian process as my starting point.

The main driving force behind pension reform: Economic sustainability

In this article, an important point of view is that the Norwegian and Swedish Pension re- forms differ from each other in certain as- pects. This is contrary to a historical tradition that can be traced back to the end of World War Two, where Norway for decades more or less blueprinted Swedish social policy solu- tions. The main driving force behind the re- forms is, however, the same in both countries: Major concerns about the economic sustaina- bility of the pension system.

The ”old” public pension schemes in both countries were designed and implemented in a period that some economic historians has labelled ”The long Sixties” (1958-1973). At this time, all curves pointed to the sky: Un- employment was low, economic growth and birth rates were high. Global climate changes as well as other serious environmental issues were still only a concern found among some pessimistic researchers, who were generally viewed as some sort of doomsday prophets by the vast majority of politicians and scientists. At the same time, the memories of the horrors

of World War Two were still very much alive. Together, these factors provided fertile soil for various welfare reforms in many Western societies, and the old age pension for all citizens – regardless of former income – be- came one of the most prominent issues. The universal old age pension was probably the most expensive of all welfare reforms, but the result was outstanding: Mass poverty among elderly was eradicated in many countries for the first time in history. As old age actually was the most important cause of poverty in Europe before the 1950’s, the introduction of (more or less) universal old age pensions also reduced the general level of poverty in socie- ty. In another article, I therefore named the universal old-age pension “The greatest suc- cess story of the 20th century”.2

The public pension schemes that were in- troduced in many European countries in these years – among them Norway and Sweden – were all Pay-as-you-go3 (PAYG) schemes. In Norway, an attempt to build a Social Secu- rity fund (“Folketrygdfondet”) was made in a short period from 1967, but nothing has been paid into this fund since early 1970s.4 The idea behind the fund was originally to finance the income-related part of the public pension scheme, but after payments to the fund stopped, it has been viewed as any general state-owned fund with no connection to Social security except for the fund’s name. The fund has, however, made favourable investments, and thus it has grown substantially through the years. In Sweden, a fund called the AP-fund was established. This fund was, however, established in order to counter an expected decline in private savings, and thus there was no intention to finance part of the pension system through this fund. The AP-fund was later on transferred to the new buffer fund after the Swedish pension reform.

One important reason for choosing PAYG instead of funding was that pension payments from the schemes could start immediately. In a fully funded scheme, the countries would have to wait a full generation (25-30 years) before adequate pensions could be paid out. Politically, this would have been impossible. After the first petrol crisis in 1973-74 and the following period of ”stagflation”5, many of the economic preconditions from ”the long Sixties” changed, and there were growing concerns over the economic sustainability of pension schemes across the western world. Birth rates declined dramatically from the mid-1970s, and they have continued to stay low. At the same time the number of years in retirement increases, while the number of working years decreases. There are three main trends influencing this development, and they

all pull in the same direction:

• Young people enter the work-force at a higher age than before

• Elderly people retire at an earlier age than before

• People live longer than before

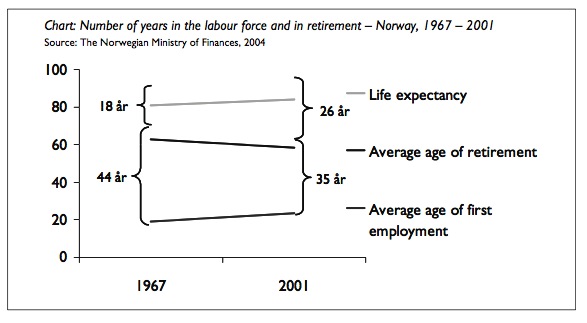

In Norway, this development means that the average number of working years has been reduced from 44 to 35 years in less than 40 years.6 In the same period, the average number of years in retirement has increased about 8 years. The chart below shows how the com- bined trends work.

This development inevitably causes eco- nomic pressure on the pension system, and thus political concern. We should therefore ask ourselves: Can any of these trends be altered through measures?

Let us start with life expectancy. Will polit- ical initiatives reverse this trend? The answer is ”no”, for quite obvious reasons. How about the other end of the life cycle – average age of full employment? The answer is most likely “perhaps, to a certain degree”. Since the 1960s, we have witnessed an educational revolution. Most jobs today require formal competence as well as advanced skills, and it is hard to imagine a return to an age when many young-

sters started working at the age of 15. Even if they wanted to, they would not have the necess- ary skills and knowledge to fill almost all positions. On the other hand, new political measures are introduced to curb further in- crease in the age of entrance into the work- force. In Norway, reforms in higher education have been introduced in order to speed up study progress and also reduce the average number of years in higher education.7 Still, it is neither possible nor desirable to reverse this trend completely. The most likely scenario is that the increase will stop.

What remains, then, are basically two types of measures: Measures to increase retirement age, and measures to reduce the value of pensions in payment. Pension reforms in both Sweden and Norway as well as in other wealthy countries deal to a large degree with these two types of measures. However, before compar- ing the actual measures taken in Norway vs. Sweden, I will present the main features of the reform process in the two countries.

Reform Process

At a superficial glance, the reform process in Sweden and Norway looks almost identical. In both countries, “Pension Commissions” were appointed. Both commissions were com- posed of leading politicians and independent experts, and their mandate was to advice their respective Governments and Parliaments on the design of the future pension system. Major stakeholders in both countries – like the la- bour market partners and the social security administrations – were not invited to partici- pate in the Commissions’ work. Both Com- missions recommended substantial changes in the respective countries’ pension systems, and recommended measures to curb future pension expenditure growth.

Here, however, ends most similarities in process between the two neighbours. In Swe- den, the Pension Commission was appointed in 1991, and delivered its report in 1994. The reform was adopted by Parliament the same year after a short but intense political process. The implementation of the reform became the responsibility for a group of representatives

from the political parties. This group would also secure necessary political support, and agree on important features of the reform. In this way, the implementation process was swift and efficient, but it has also been criti- cised for being more or less closed to public debate and to various interest groups and stakeholders.

In Norway, on the other hand, the process so far has been slower and far more incremental. The Pension Commission was established in

2001 and delivered its report in 2004. The report was then submitted to a broad hearing, including both various stakeholders and the administration in the process. In December

2004, the centre-right Government presented a White Paper. 8 This White Paper presented only the recommended principles for a pen- sion reform, no figures or numbers at all. The paper was sent to Parliament in May 2005, and the Parliament adopted a set of principles for the new pension system. The decision in May 2005 still held no figures or numbers. Instead, the detailed features will be decided through further political process. In October

2006, the Government presented a second White Paper 9 on a reformed public pension scheme, and it will be followed by new legis- lation in 2007. For parts of the reform, e.g. the future of the disability pension, a decision cannot be expected until 2008.

In addition to a more incremental political process, the administrative implementation of the Norwegian reform is kept more sepa- rate from the political process than the case was in Sweden. In Norway, a Pension Pro- gram was established in November 2005, under the auspices of the National Insurance Administration.10 The scope of this program is purely administrative: The program will develop new ICT-solutions, along with new administrative structures for the future pen- sion administration. The program will also be responsible for public information on the con- tents of the reform. The program, however, plays no significant role in the ongoing poli- tical process.

As we see, the political process will continue far into 2007, maybe even into 2008. Yet, certain important decisions have already been made, so it is possible to compare some of the results of the reform processes in the two neighbouring countries.

Reform results

As Norway is still in the middle of a pension reform that will be in effect from 2010, it is not possible to compare the two reforms in full for a number of years still. In particular, it is impossible to compare macro as well as micro economic impacts of the reforms. Further- more, we cannot compare all aspects of flex- ible retirement. Norway will have flexible retirement, but the details remain to be decid- ed. I will therefore concentrate on three im- portant structural elements in both the Swed- ish and Norwegian reforms:

• The PAYG financed public old age pension schemes.

• Mandatory supplements to the PAYG fi- nanced public old age pension schemes.

• Measures to secure economic sustainabil ity.

The PAYG public old age schemes

In Norway, a new model for the public old age scheme will be introduced from year 2010. The Government’s white paper suggests that this model will have many features in com- mon with the PAYG part of the new Swedish old age scheme. The Norwegian scheme will have two tiers: An income related benefit and basic security for everyone.

The new Norwegian scheme, like the Swed- ish, is based on the principle that work should pay. An important tool is strengthening the

connection between contributions and bene- fits in the income related benefit. The most important change from the present system is that all earnings will be taken into account when the benefit is calculated. Today, the upper age limit for earning pension credits is

70 years. This age limit will be abolished. There is also a lower limit of 17 years. The lower limit may be kept or it may be abolished together with the upper age limit, but the practical impacts of the lower limit are small, as almost no one has substantial income from work at the age of 16 or younger.

In the present scheme, an average of the 20 best years of income is used to calculate the income related pension. In the new scheme, various credits will partly compensate for years with low or no earnings. The existing pension credits for care work 11 will be im- proved. There will also be credits for manda- tory military service. Furthermore, it is sug- gested that unemployment benefits will be credited on the basis of income before unem- ployment, not on the basis of the benefits (that are substantially lower). Sickness and disabil- ity benefits will on the other hand be regarded as pension earning income at face value. In general, this credit system resembles the present Swedish pension credits, though there are some differences.

In the Norwegian scheme, basic security will be provided by the Guarantee pension, like in Sweden. The level of the Guarantee pension will, according to Parliament, be “the same level” as the present minimum pension. There is, however, one very important change from today: The Guarantee pension will not be fully reduced against the earned income pension. Instead, it will be reduced at a certain rate.12 This change has an important positive effect for low-income earners: In the present scheme, many low-income earners actually retire on a minimum pension at the age of 67. This is especially the case for long-term part- time workers.13 At the same time, a person

with no work record at all receives the same amount, i.e. the minimum pension. This effect occurs because the present scheme is com- posed of a basic pension plus an income related pension or a special supplement. If a pensioner is entitled to an income related pension below the level of the special supple- ment, she will receive the income related benefit plus part of the special supplement – meaning the special supplement consumes her entire income related pension.

In the political language, this effect is called “The Minimum Pension Trap”, and it seems to be political consensus on removing it. With the model put forward in the White Paper of October 2006, low-income earners will al- ways receive a pension above the minimum level.14

In the new scheme, it will be possible to draw an income related pension from the age of 62 at a reduced rate. The Guarantee pension will be payable from the age of 67, the same as the present pension age. In Sweden, these age limits are 61, respectively 65 years. This means that in both Norway and Sweden ”pension age” as a defined concept has been abolished, except for the Guarantee pension (i.e. basic old age security). In Sweden, the former pen- sion age of 65 still remains the upper age limit for social security benefits like unemploy- ment benefits and disability benefits. The reason for this upper limit is that the individ- ual at this age will be entitled to an old age pension. In Norway, this upper limit is logi- cally 67. The Government is aware that flex- ible retirement may have consequences for the transfer from disability and unemploy- ment benefits to old age pension, but the detailed solutions will probably not be decid- ed until 2008.

Thus, we see that many of the principles and main features of the new public old age scheme in Norway are similar to the ”new” Swedish scheme, although the schemes will differ from each other in some aspects. The Norwegian

and the Swedish reformers have, however, chosen different paths regarding the two other structural elements discussed in this article: Measures to secure economic sustainability, and mandatory supplements to the PAYG financed public old age schemes.

Mandatory supplements to the PAYG financed public old age pension schemes

Both countries have introduced mandatory schemes that supplement the public PAYG old age schemes. The Swedish solution is that the Premium Pension is a mandatory contri- bution defined scheme that is funded, with individual investment choices for the contrib- utors. In addition, more than 90 % of Swedish employees are covered by voluntary occupa- tional schemes.15

In Norway, the question of mandatory sup- plementary schemes turned out to be one of the major debates within the Pension Com- mission. The Commission actually split into three fractions, none of them able to win support from the majority of the Commission. One fraction opted for a solution similar to the Swedish Premium Pension, one fraction want- ed mandatory occupational schemes, and one fraction wanted no mandatory supplementary schemes at all. In its White Paper in December

2004, the Government suggested mandatory supplementary schemes, but proposed two alternatives (either individual accounts, like the Premium Pension, or schemes), but gave no real recommendation on either alternative In spring 2005, it became evident that most important actors in the pension field wanted mandatory occupational schemes, and the Parliament adopted this solution in its deci- sion on future principles May 26 2005. An Act on mandatory occupational pensions came into effect on January 1 2006. Norway had modernised its legal framework on voluntary occupational pension plans as late as 2001,16 and the new legislation is built on the 2001

Acts. In addition, the agreements on occupa- tional pension plans for municipality employ- ees also became mandatory, with no changes in existing schemes. It therefore seems rea- sonable to say that the new mandatory occu- pational scheme is an extension of existing schemes, but no clear break with the past. The most important change is that from 2006 on,

100 per cent of the employees are covered by supplementary schemes, while between 60 and 70 per cent were covered under the volun- tary regime.

The Act on mandatory occupational pen- sions has not solved all questions related to occupational pension plans. The Act defines minimum requirements for the schemes, but many schemes provide a far higher benefit level than these minimum standards. This is especially visible in the public sector schemes. The parliamentary decision of May 26 means that the public sector schemes will continue to be defined benefit schemes, with benefits that equal 2/3 of the employee’s final salary. However, the longevity coefficient will also be introduced in the public sector occupation- al schemes from year 2010. The pension plan is legally a part of public sector employee’s work contract, and the details of the future schemes will therefore partly be subject to wage negotiations.

Sweden and Norway have thus adopted different solutions for mandatory supplemen- tary schemes. Both solutions mean that the volume of services and capital for private financial institutions increase as a result of public pension policies, but in all other as- pects the solutions differ from each other. In Sweden, politicians chose to introduce a prin- ciple of mandatory individual accounts, with a complete new regime (The Premium Pen- sion Authority) to monitor both the contribu- tors and the more than 700 investment funds available to the Swedish people. In Norway, the solution was to extend the existing ar-rangements by making them mandatory. Now new authorities have been created – The Banking, Financial and Insurance Registry (Kredittilsynet) monitors the institutions that provide mandatory occupational schemes, just as they did when the schemes were voluntary. It would be interesting to see a comparative analysis on the Norwegian and Swedish man- datory supplementary schemes, but the Nor- wegian solution will need to function for some time before it is possible to make such an

analysis.

Measures to secure economic sustainability

The main driving force behind the reforms in Norway and Sweden is the same: Major con- cerns about the economic sustainability of the pension system. Measures to secure sustaina- bility have therefore been crucial in both re- form processes. Some of the measures are similar in both countries, but the two reforms differ on at least one crucial point.

Let us, as a starting point, look at the types of measures taken to reduce costs in a pension scheme. Two main types of measures are available: Measures to make people work longer (meaning both increased productivity and fewer years in retirement), and measures to reduce the total amount of money paid out to the pensioners. The alternative to reducing costs is of course to increase the schemes’ gross income. This means higher contribu- tions, which does not seem to be a real option in either country. Measures taken are thus measures to reduce costs.

In the Norwegian reform, there are primari- ly two measures that will bring better eco- nomic sustainability to the scheme: The intro- duction of a longevity coefficient, together with changed indexation formulas. The other elements of the reform will hardly reduce costs at all, compared to the existing old age scheme.

The longevity coefficient means that bene- fits are adjusted as life expectancy changes. If a person e.g. retires at the age of 67 in 2030, and life expectancy has grown two years since

2010, he will have to work about 1,5 years longer to receive the same benefit as a 67- year-old person retiring in 2010 (all other things being equal). The individual can there- fore counteract the effect of the longevity coefficient by working longer before he or she retires. On the other hand, if he or she retires at an earlier age, the benefit is reduced be- cause of this coefficient.

The other measure to secure economic sus- tainability is changing the indexation rules for pension benefits. Today, Norway has quite favourable indexation of benefits (at the same rate or higher than wage increase). In the future, benefits will be indexed 50 % wage and 50 % price, while the Guarantee pension will be indexed at a more favourable rate than the Income pension. This change is expected to reduce the growth in future costs substan- tially. Contributions will still be indexed by wage growth

The same measures (the longevity coeffi- cient and changes in indexation) have been introduced in Sweden, although indexation of pension benefits in Sweden has a different profile, as the indexation of the income pen- sion is more favourable than for the Guarantee pension. The former is adjusted annually by wage growth minus 1,6 %, while the latter is indexed annually by growth in prices.

In addition to these two measures, Sweden has also introduced a third measure, which will not be paralleled in Norway: The Auto- matic Balancing Mechanism, or “The Brake”. The Automatic Balancing Mechanism is designed as a means to maintain contributions at the same level in all future. When contribu- tions exceed pension payments, the surplus amount is transferred to a buffer fund. The basis of this buffer fund was the assets from the AP-fund. These were transferred into a

pension buffer fund when the reform came into effect in 1999. At present, the fund’s assets are about SEK 700 billions (EUR 80 billions). When the number of pensioners increases, it is, however, expected that the annual contributions will no longer be suffi- cient to cover the benefits. If, then, the value of the annual contributions plus the value of the buffer fund is lower than the actual pen- sions paid out, the “brakes” are put on, so that the payments to each individual pensioner is reduced according to a formula. The Auto- matic Balancing Mechanism actually trans- fers the risk of financial imbalance in the pension scheme from the State – which carries all financial risk in a pure PAYG system (through the taxpayers) – to the individual pensioner.

In the Norwegian reform, there will not be an automatic balancing mechanism similar to the Swedish solution. Instead, Parliament in December 2005 decided to transform the two major state-owned funds (The National Insur- ance Fund, and its “bigger brother”, the Petrol Fund) into a public pension fund. The deci- sion was put in effect from 1 January 2006. The new fund will be split into two parts. One will be invested abroad, and one will be in- vested in domestic industries. This decision means that the financial governance of the fund will continue more or less as before

2006. What is novel is that the Pension Fund now, like Ulysses, is firmly tied to the mast of future pensions, thus escaping from the de- ceptive song of the Sirens, who sing about a multitude of good ways to spend this for- tune.17

The new Pension Fund will be a buffer fund. This means that Norwegian citizens cannot claim an individual right to his or her share of the fund. The fund today has a value of approximately NOK 1700 (almost EUR 200 billions), making it the world’s second largest fund.18 The fund will play a different role from the Swedish buffer fund. The detailed mechanisms for transferring means from the fund into the pension schemes have not yet been decided, what is clear, however, is that there will be no automatic balancing mecha- nism like in Sweden. Here, we find the most important difference between the principles adopted in the two neighbouring countries. The Norwegian reform also transfers part of the risk from the State and the taxpayers to the individual through the introduction of the longevity coefficient19, but the individual can still (at least to a certain degree) control this risk by working longer before retirement. The financial risk of the old age pension scheme is still carried in full by the State in Norway. In Sweden, this risk has in principle been shifted to the individual.

Conclusion

The pension reform processes in Sweden and Norway may look almost identical at a super- ficial glance. On closer inspection, however, important differences emerge. Even though the Norwegian process is far from complete, a preliminary conclusion is that the Norwe- gian pension system will remain a traditional social insurance system even after the reform, while the reformed Swedish system has more in common with a traditionally funded sys- tem. Even if the reformed Swedish system is a pay-as-you- system, part of the financial risk is transferred from the State to the individual. This is not the case with the Norwegian re- form. This difference in outcome of the two countries’ reform processes is probably best explained by different perceptions on future

”crisis” in the old age pension system, and of course, the different national economic posi- tion of the two countries. By transforming the petrol fortune into a pension fund, Norway has secured a financial buffer for future pen- sion payments that is already six times as high per capita than the Swedish financial buffer.

Notes

- 1 In this article, I mostly discuss the pension sys- tems in both countries, as both reforms have a scope that is broader than the public schemes. When the term “scheme” is used, it always refers to a specific scheme, e.g. “The Norwegian public old-age scheme”.

- 2 ”Adresseavisen” 7.7.2002

- 3 Pay-as-you-go means that contributions levied one (fiscal) year are used to pay benefits the same year. The alternative to PAYG is a funded sys- tem.

- 4 The fund still exists, and from January 1 2006 it is part of the new public pension fund.

- 5 “Stagflation” is a term that was coined in the 1970’s. It describes a situation where economic stagnation and high inflation occurs simultane- ously. Stagflation posed a major challenge to the Keynesian economic theories that prevailed in Scandinavia in the post-war area.

- 6 It should, however, be noted that the chart omits one important aspect: The number of people in the work force, and thus the total number of hours worked has increased substantially since 1967, mainly because of increased female employ- ment. This makes the picture look better. On the other hand, employment rates in Norway (and even more in Sweden) are high (almost 80 % for women and men combined), so that the labour reserve is low in both countries. This means that the increasing number of years outside the work force (at both old and young age) is still a matter of concern.

- 7 On average, academic studies in Norway used to last longer than in most other countries (4 1/2 years for lower degrees, 6 years for higher de- grees in traditional university education). A re- form two years ago put Norwegian universities in line with the rest of Europe.

- 8 Stortingsmelding nr. 12 2004–2005: “Trygghet for pensjonene”

- 9 Stortingsmelding nr. 5 2006–2007: “Opptjening og uttak av alderspensjon i folketrygden”

- 10 The NIA is presently undergoing major changes, as it was merged with the Labour Market authori- ties from 1 July 2006. I will not go into details about this change in this article.

- 11 Both care for children and for adults (sick/and or elderly people) is credited.

- 12 The Government suggests an 80 % reduction rate. The rate has not yet been decided.

- 13 It should be well known that this segment of the work force is almost exclusively female.

- 14 The “Minimum Pension Trap” has (at least) two dimensions. The first is benefits (= distribution among groups of pensioners). The second, not so often debated, is contributions (= distribution within the workforce): It can be argued that the present system, where contributions are levied on all income from work, means a rather strong element of regressive taxation.

- 15 OECD 2005: ”Pensions at a glance”.

- 16 Lov om foretakspensjon (= The Act on Corpo- rate pension plans) and Lov om innskuddspensjon (= the Act on contribution defined occupational pension plans).

- 17 Not all North Sea oil and gas revenues are put into the Pension Fund. Between NOK 70 and 80 billions (EUR 9 to 10 billions) are spent in the annual State budgets.

- 18 The value of the Norwegian Pension Fund is almost six times the value of the Swedish Pen- sion Fund per capita, and it grows at a much higher pace than the Swedish fund. It is expected that the value of the Norwegian Pension Fund will exceed NOK 2 100 billions (EUR 250 bil- lions) by the end of 2007.

- 19 ”Pensionable age” (67 years in Norway, 65 in Sweden for the Guarantee pension) was origi- nally set based on life expectancy. In the first social insurance scheme (Germany, 1881), Bis- marck set the pensionable age at 65 years. This scheme covered only industrial workers and the average life expectancy for this group in 1880 was 58 years. Following the same logic, pension- able age in Norway and Sweden today would be 85+ (!). 65, however, quickly became the norm in most social insurance schemes based on contri- butions from work, while 70 (later 67) was the norm in universal old age schemes. Pensionable age has not been changed in accordance with increasing life expectancy, and today holds no connection to life expectancy figures.

* * *

This article is one in a series about the Swedish pension reform. Earlier articles published in the NFT are written by Hagberg and Wohlner (4/ 2002), Könberg (1/2004), Casey (2/2004), Barr (3/2004), Lezner and Tipperman (4/2004), McGil- livray (3/2005), Scherman (2/2006), Settergren (3/2006), Rasmussen and Skjødt (4/2006). These articles can all be found at www.sff.a.se/?avd=forlag&sida= pension. lasso