Getting practical with wearables

As digital data becomes more available and accessible, life insurers are exploring how to

use this alternative data to assess applicants. Risk assessment, which continuously evolves

over time, now has the potential to move to the next level with the arrival of this alternative

data ‒ which is usually easier to access and can enhance the underwriting journey.

However, different is not always better and it is important to understand and test the use

of alternative data.

Using physical activity as an example of alternative data, we dive into five different

applications of alternative data within the life insurance market. We explore how physical

activity data can prove to be successful when used either to augment the existing

underwriting journey or when used on an ongoing basis such as for dynamic underwriting,

resulting in improved accuracy of mortality rates and enhanced predictive power. However,

it is less successful when used to replace or substitute existing underwriting information

since omitting information can lead to reduced predictive power. A possible future

approach is to use physical activity data to personalise the customer journey for applicants

in a way which can result in increased conversion and sales rates.

Lastly, when using alternative data, it is important to do so first in a test and learn

environment with defined goals and criteria. Legal and regulatory considerations are also

essential to any use of alternative data.

Introduction

Underwriting has always involved practical information gathering between the insurance

company and the applicant. The insurer typically wants to know as much as possible about

the risk profile of the applicant while not jeopardising the opportunity to convert a sale.

Historically, this underwriting process has focused on a combination of self-reported

questions, medical reports, and medical tests. However, in recent years, digital data such

as wearable and smartphone data have become more prevalent and easier to access.

Consumers also want to engage more and be recognised (or rewarded) for their lifestyle

which may improve their health management. As a result, life and health insurance

underwriters are contemplating how to use this alternative data to risk-assess applicants.

This paper will focus on how to apply use lifestyle risk factors with a specific focus on

physical activity. It will also run through some real-life case studies and results where

insurance companies are using physical activity in underwriting.

Physical activity

Physical activity is probably the most common health metric which is being monitored and

tracked by people on a regular basis today. It has been shown in many studies to improve

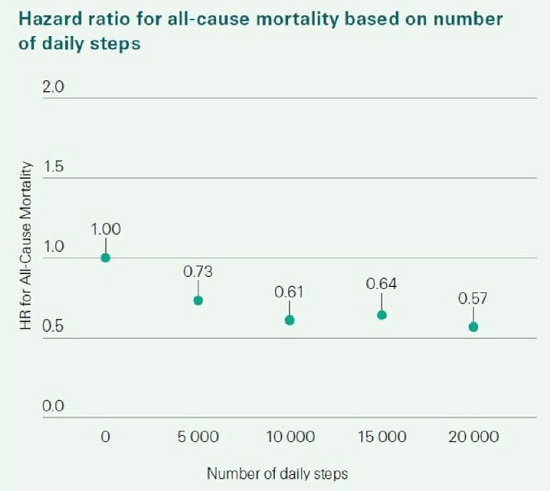

health with better mortality and morbidity outcomes. The recent collaboration between

Swiss Re and Oxford University, using UK Biobank data, confirms this. Because of this

health effect, and the ubiquitous availability of physical activity data (particularly steps),

insurance companies are looking to use it in risk assessment.

Evidence of steps based on a research study collaboration between Swiss Re and Oxford

University:

Although steps data is typically easy to track and is recorded by almost all smartphones

and by all wearables, it is however limited in its tracking of a person’s total physical activity

as it ignores all other types of physical activities. Total physical activity instead consists of

many different activities such as running, walking, climbing stairs, swimming, cycling, etc.

It would be preferable, though not compulsory to track all of a person’s physical activities.

To be able to compare physical activity across these different activities the

metric Metabolic Equivalent of Task (METs) is typically used. METs represents the amount

of energy that you expend when doing an activity compared to that when at rest, whereby

rest is considered to be equivalent to 1 MET. METs are calculated using the intensity,

frequency, and the duration of activities allowing for comparison between different types

of activities. This paper will focus on the use of METs. To put it in perspective, walking at

an average pace (i.e., doing steps) has a MET value of 3, average speed cycling has a MET

value of 6, and average speed running has a MET value of 8. Therefore, five 30-minute

sessions of each activity per week will accumulate to different total physical activity

MET/hours per week of: 7.5 for walking, 15 for cycling and 20 for running.

Why the desire to use wearable data in risk assessment?

Risk assessment has developed and improved over time as more and more health data has

become accessible. Ubiquitous wearable and smartphone data has accelerated the focus

on digital risk assessment. This has primarily been driven by a desire to either get a more

complete picture of a person’s health and thereby offer more competitive premium rates,

or to shorten the risk assessment process and provide customers with a less onerous

onboarding journey.

Physical activity along with the other lifestyle risk factors are now being used to improve

the risk assessment process. Their availability is also creating opportunities for life and

health insurers to engage with consumers in new ways, simplify the onboarding and

underwriting journey, and offer improved tailored propositions. The hope is that this will

lead to improved new business volumes, higher conversion rates and lower lapses.

Insurance companies are eager to explore this data as they recognise that it has the

potential to benefit all parts of the value chain from:

· consumers who have increased health awareness and tracking of their activities

and thereby want to be rewarded through receiving more personalised experiences

· insurers who want to create attractive product propositions and improve their risk

assessment, are seeing the explosion of health apps, wearables, e.g., the Apple

Health kit, as well as the proliferation of credible data, as an opportunity to do this

· society who could reap the benefits of improved health awareness, better wellness,

and reduced global burden of disease

· brokers and advisers who may be able to offer quicker, tech-enabled, and cheaper

insurance offerings to consumers

Key considerations in understanding the value of alternative

data

While there is a large amount of excitement around using wearable data to innovate

underwriting, to unleash the full potential of this alternative data and use it meaningfully is

not as simple as it may seem. It is important to understand the validity and protective value

of this alternative data relative to established practices. We also need to consider how to

interpret this data in a fair and responsible way.

Key to assessing any alternative data in risk assessment is analysing its potential to

provide enhanced commercial value.

Some key considerations with the new data are:

· Is it quicker to access, allowing for greater automation and faster processing?

· Is it cheaper to implement and run?

· Can it provide greater accuracy or predictive value?

· Is it easy to use and based on data or technology that is widely available?

These questions may appear straightforward but many self declared "underwriting

innovations" struggle to answer yes to all of these considerations. Some may offer

incremental increases in speed or accuracy, but come with increased costs due to

increased risks. These questions need to all be considered together to assess the overall

business case for using the alternative data.

Using physical activity data from wearables as an example:

five applications

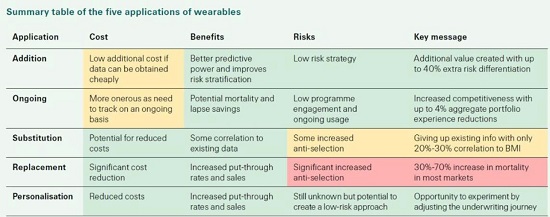

There are five common applications where we, at Swiss Re, see wearable data being

deployed. These applications occur across different risk factors; however, this paper will

focus on physical activity (measured in METs).

The five applications of physical activity data are as follows:

1. Addition: Augmenting current risk assessment with METs to better stratify risk

2. Ongoing/Continuous: Using METs for dynamic underwriting

3. Substitution: 1-for-1 risk factor replacement, e.g., replacing BMI with METs

4. Replacement: METs used in place of several health risk factors

5. Personalisation: Using METs to pre-select customers for different UW journeys

Addition: Is it worth adding METs into the risk assessment

journey?

Our internal research shows that METs have been shown to provide additional predictive

power and risk prediction due to their correlation with better mortality and morbidity

outcomes. This in turn helps to improve risk stratification and has the potential to select

and attract more physically active applicants. The selection is beneficial as it results in an

insurer having a portfolio of policyholders who on average have lower mortality rates, and

this typically allows them to offer more competitive premiums in the market through this

additional risk differentiation.

However, the value of METs also depends on several other factors such as the length and

accuracy of the data as well as the baseline starting MET levels of the group of customers.

If the group of customers has a high starting baseline level of METs, this will reduce the

potential for mortality improvements.

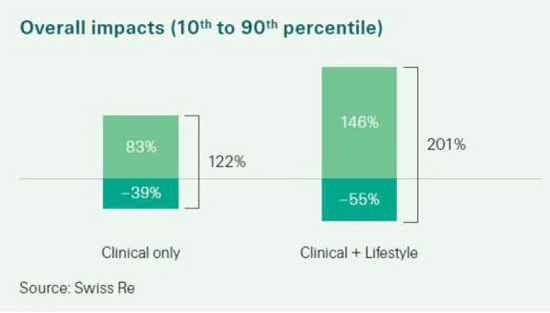

When expanding this to other risk factors, the level of underwriting risk differentiation can

be significantly enhanced. The graph below, based on our internal research on a mortality

risk pool, illustrates the potential to increase the range of risk differentiation when adding

several lifestyle risk factors into risk assessment. It compares this range under two

scenarios: 1) when only using clinical factors and 2) when using both clinical and lifestyle

factors. The range is calculated by looking at the minimum and maximum range of each

risk factor whereby each one individually would still place the person in a standard

underwriting pool.

Under the first scenario when only using clinical factors such as (BMI, blood pressure,

cholesterol and HBA1C), the range of risk differentiation is 122% (from -39% to 83%). This

range increases on both sides to 201% (from -55% to 146%) under the second scenario,

when also including lifestyle risk factors such as physical activity, nutrition, sleep, and

mental wellness.

It is important to note that a wider risk differentiation range does not mean that a portfolio

will suddenly have better mortality rates.

It is still a zero-sum game whereby the consumers who receive additional discounts for a

healthy lifestyle should be balanced against less healthy lives who may receive additional

loadings. Insurers will therefore need to create additional value by attracting healthier lives

through the additional risk stratification and thereby generate better mortality rates.

One of the additional goals of engaging with consumers by using wearable or lifestyle data,

is the potential to help policyholders improve both their health and insurability by using

linked wellness and lifestyle programs. This should however, the benefits of additional risk

differentiation (e.g. the potential to positively select healthier applicants) need to be

considered against the costs and ease of obtaining this data on a one-off basis, as well as

the credibility of the data, the robustness of the historical data, and other competitive

pressures.

Ongoing: Is there a future for dynamic underwriting?

Dynamic underwriting has gained attention in recent years, even before the explosion of

wearables. The idea of policyholders engaging with and improving their clinically

modifiable risk factors (e.g., BMI or blood pressure) to gain some financial or other reward

benefit, has been around for over a decade.

Wearables promise a more automated and consistent flow of information to update

modifiable lifestyle risk. METs have been shown to be an excellent fit for dynamic

underwriting; the data is widely available and easy to access. Over the medium to longterm,

the predictive power of tracking METs makes it easier to identify, price for, and drive

healthy behaviour change which can help to reduce a customer’s risk or prevent their risk

worsening. METs can also be used to promote policyholder wellbeing on an ongoing basis,

allowing insurers to incentivise and reward positive behaviour.

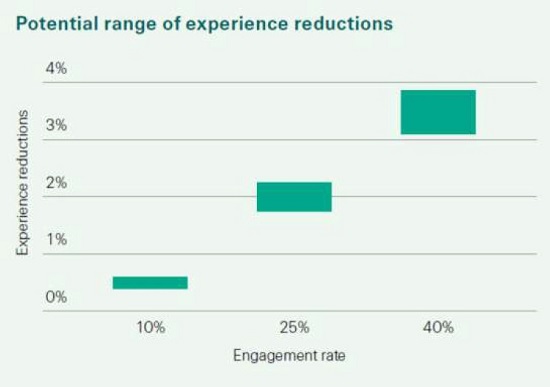

Our global internal data research shows that health and wellness engagement platforms

that track and reward particular levels of METs, as well as run annual health assessments

that track other clinical and lifestyle risk factors may be able to see aggregate mortality and

lapse experience reductions of up to 4% across the entire insurance policy book, with a

substantial proportion of the benefit coming from getting customers to positively change

their behaviours. This is shown in the graph below.

Substitution: Can METs be a 1-1 risk factor replacement?

Although METs as a risk factor has some protective value, research shows that it cannot

simply replace existing underwriting risk factors. If we were to replace BMI with METs,

data shows that this approach could lead to important and meaningful gaps in risk

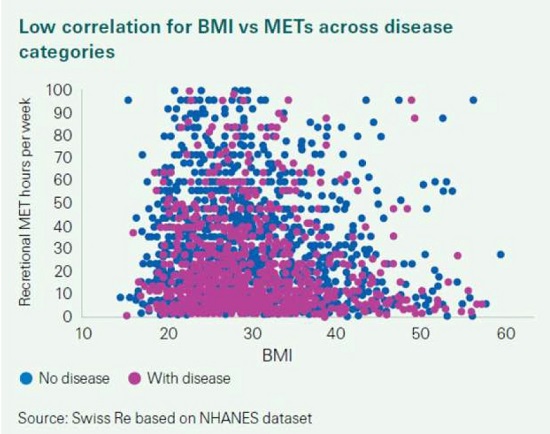

assessment. In fact, the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)

database and UK Biobank both show low overall correlation, as is shown in the graphs

below:

· < 30% on NHANES between BMI and METS even after allowing for diseases

· 20% on the UK Biobank between BMI and step count when using accelerometer

data.

As a result, replacing BMI or steps with METs could result in lives with higher BMI levels

selecting into the product. The level of anti-selection will though depend on factors such as

competitive considerations, relevant market disclosure rates, target audience (e.g., age)

and the range of BMI values.

There are certain situations where insurance companies would typically be more

supportive of a substitution approach, e.g., where several mitigants or pre-selection may

exist, such as people who are originally part of a wellness program, or young athletes. Also,

in a market with poor BMI disclosure, using more objective wearable METs may actually

help to improve risk selection.

Replacement: Can METs completely replace traditional clinical

risk factors and medical history – are we ready?

Some InsurTech companies promote a view that METs alone are as predictive as current

underwriting. The view is that by collecting METs, age, gender and only a couple of other

risk factors, they can create a portfolio that in some circumstances is at least 95% as

predictive as current underwriting and hence a shorter underwriting approach could be

adopted.

Although the frequency of inaccuracy can be low, the severity of the incorrectly priced risks

can be very high. As an example, the NHANES data shows that there is a low correlation

between people having a disease and METs (< 20%) as shown in the graph below. This

means that underwriting that relies solely only METs, will result in people with medical

diseases being added into the standard underwriting pool without being priced correctly.

The potential for anti-selection can also increase significantly if diseases are not being

considered. In fact, our internal data research shows that this anti-selection increases

claims costs by as much as 30-70% in most markets and rises to a 100% or more in

markets which offer preferred products.

Legal and regulatory considerations

Legal and regulatory attention is growing when it comes to using alternative data in risk

assessment and algorithmic underwriting approaches. Therefore, it is paramount to

consider these aspects.

Some specific challenges include:

· how to treat customers fairly in pricing, underwriting, and product structure with

the alternative data and ensure equitable risk selection for those that do not have

such data available

· whether the use of the alternative data creates any unfair discrimination, e.g.,

across ages, income status based on access to wearable devices, ethnicity, etc.

· bias due to data collection opportunities

· lack of transparency in “black box” risk selection algorithms

· use and transfer of personal data for risk selection purposes

· how non-disclosure or misrepresentation might work in a world of alternative

underwriting data and the ability of insurers to challenge misrepresented or

erroneous data (i.e. in wearables)

· how best to encourage of customers to use wearable apps and share their data

· how to inform and get consent from applicants to use the data in risk assessment

· ensuring data privacy considerations

· not create disadvantages for certain segments of society who do not have access to

wearable devices, e.g., due to affordability